Ghost Dance

Or The Czar's Black Angel

'Are you cold, my children? Are you cold?'

Chapter 1

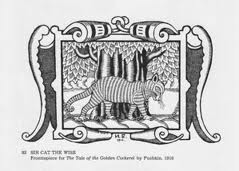

In a place far distant from where you are now grows an oak tree by a lake.

Round the oak's trunk is a chain of golden links.

Tethered to the chain is a learned cat, and this most learned of all cats walks round and round the tree continually.

As it walks one way, it sings songs.

As it walks the other, it tells stories.

This is one of the stories the cat tells.

-*-

I tell (says the cat) of the Northlands, where, in the long, dark winter, the white snow falls out of the black, black sky. Soft, silent, it falls through the branches of the pines and birch, and mounts, thin flake on thin flake, until the snow lies ten cold feet deep, and the silence is frozen to the darkness.

This (says the cat) is the land where that white, sharp-backed horse, North Wind, carries Granddad Frost swiftly through the trees. The old man breathes to the left

and right, and what his breath touches is blasted and withered, and his rasping voice whispers, 'Are you cold, children? Are you cold?'

I tell (says the cat) of a gyrfalcon flying - a bird the colour of snow in darkness, flying above snow and through darkness. It turned in sweeping circles, it gyred, and its sickle-winged shadow scudded before it over the moonlit snow far beneath.

The gyrfalcon looked down and saw a flat circle of the Earth tipped up to its gaze. A circle of Earth gleaming white, but marked with black rocks, with black trees, and all growing smaller as the

falcon gyred upwards; all growing greater as it spun down. The only sounds the falcon hears are the soft huff of wind under its wings, and its own cry, thin and sharp as wire drawn from ice:

Keeeeya! Keeee-ya!

A gyrfalcon's eyes can outstare the sun, and now they pierced the winter darkness. It saw a tree, and its eyes stared, and saw the cones in its branches; and stared, and saw each needle leaf. And

stared, and saw the mice running up the trunk.

Its eyes stared down, and saw the rocks; and stared and saw the cracks in the rocks; and stared and saw the voles that hid there. It stared down and saw the fox making tracks across the snow. It

saw the fish beneath the ice.

It wheeled in the sky and looked down and saw the tents of the reindeer people, and the reindeer, and the wolves following, and the ever-hungry glutton hurrying among the trees. It saw the

snow-rabbit and the lynx and the bear.

But of all these things, trees and people, deer and wolves, fish and lynx, fox and bear, the gyrfalcon saw fewer, far fewer than before. And it saw bloodied places in the snow, and twisted,

frozen bodies in traps; and the cut stumps of trees. Keeee-ya! Keeee-ya!

Then the gyrfalcon's eyes sharpened on what it searched for, and it wheeled in the cold sky and circled down. Below, a small line of men, black against the snow, slid on skis through the pines. Lower the falcon gyred, and lower, staring on the men.

I'll tell of the men (says the cat). They were hunters, and hungry. The snow was so deep that they were raised high among the tree branches and skimmed through them like birds. All of them looked

like fat old men, with their round bodies and their white beards - but their fatness was the thick, warm padding of their clothes; and their beards were not white with age, but with ice frozen to

the hair. All of them skied with their heads ducked low, to keep their faces from the scraping of the wind-blown ice, and they gripped bows in their mittened hands, and wore hoods or tall caps

with flaps to cover their ears. Quivers of arrows rustled and thumped at their sides, but no game. They had caught nothing.

They peered from side to side as they went, for the wind carried a load of ice-crystals that rattled and crackled in the cold air, and made a shifting white, grey, ice-blue veil before their

eyes. The wind would drop, and let the ice fall, crackling, to the snow, and the black trees would stand out clear against the white, the silver stars bright against the black. But then the wind

would lift up the ice and snow once more, and the stars dimmed, and the trees seemed to shrink or grow, or even to leave the Earth and walk, when seen through that shifting, icy cloud.

A whiteness swooped at the men and they skidded to a halt, snow spurting from their skis. They ducked and cried out as the gyrfalcon came swinging towards them again. With upraised wings, it dropped from the sky into the snow, and turned into - what? Too small for a man. A boy? The figure straightened from a crouch and stood before them, its booted feet denting the frozen surface of the snow. The hunters reached to their quivers for arrows, and fitted them to their bowstrings.

A lad - or a girl. A girl, or a lad, who had dropped out of a tree - or out of the sky. A lad, or a girl, alone, so far from any camp or settlement - and dressed, in this cold and darkness, as if

for a stroll on a summer evening.

Boots, yes, hide boots like theirs, embroidered and patterned; but above the boots only a tunic and breeches of thin reindeer hide, stitched with brass rings, with tiny mirrors that flashed a

dimmed white light, with bunches of tiny bones and bunches of white feathers.

But no gloves and no hat - the stranger's long black hair blew about in the wind, and was quickly turning white with snow, as if this youngster were growing old in moments.

The hunters knew that no one living could endure such cold, dressed so lightly. They dared not take their eyes from the creature to look at each other, but all of them feared, in their own minds,

that this was the ghost of one frozen to death, searching for others to soothe to freezing death in the snow.

The stranger came closer and, in the light reflected from the snow, they could see the face of one of their own people. But it could have been the face of a pretty boy or a handsome girl. The stranger stretched out a naked hand and placed it on the arm of the hunters' leader.

'Are you cold, Uncle?' the stranger asked, just as Frost is said to ask. The voice was that of a boy, but croaking and quiet, as if the cold had withered it. 'I've been sent to find you.'

The hunters looked at each other, hoping one of them would know what to do. Some bent their bows further, ready to send an arrow into the ghost. Their leader, with the stranger's hand still on

his wrist, looked into the boy-girl's face and asked, 'Who sent you to find us?'

'My grandmother.' The hoarse voice seemed surprised. 'Are you not searching for a shaman? I'm sent to bring you to her.'

The hunters gasped, sending puffs of their white breath into the darkness before their faces - breath which froze into icicles on their beards. They drew back from the stranger - all but the

leader, who stood as if the hand on his wrist held him to the spot. Those with bent bows hastily let them down, took the arrows from the strings and put them back into their quivers as if no

thought of shooting at the shaman's grandchild had been in their minds. It is never wise to offend a shaman. But they were not made happy by the stranger's words.

'Go with this forest ghost? Too dangerous!'

'We must! Haven't we proved a shaman can't be found by looking? Haven't we looked and looked and never found a trace of one?'

'It's an ice-devil! It will breathe in our faces and freeze us to death!'

The leader, still standing face to face with the stranger, said, 'How can we tell if we can trust you?'

In the hoarse voice that seemed always about to choke into silence, the young stranger said, 'If my grandmother meant to hurt you, Uncle, she could have done it without sending me within reach of

your arrows. If I had meant to hurt you, I could have done it before you ever saw me.'

The leader nodded. 'Go on. I'll follow.' He slithered around on his skis and said to his friends, 'You can stay here, or go home, if you like.'

'I'll come!' said one.

'And I!' said another, shamefaced, and the rest grumbled that they would come too.

The young stranger gave a wide, white smile, turned and ran away over the snow. The frozen surface crunched and creaked beneath the running steps, but did not break; and the hunters pushed with

their bows and slid swiftly after on their skis as the running figure vanished in the snow-mist and waveringly reappeared.

The runner leaped, spread arms that feathered and beat and lifted - and the white gyrfalcon was flying, sweeping high and circling and swooping down to flash white before their faces.

Keeee-ya! It led them, a moon-white bird, through the black trees, over the white snow, under the black sky.

The hunters followed, skimming over the snow, the leaders intent on keeping the bird in sight. Those who came behind, with less to think of, were more nervous, and looked back into the cold and

dark. The wind followed them, whispering, in the rattle and rustle of its shaken ice-crystals, 'Are you cold, my children? Are you cold?' The falcon led them through the trees, through

the snow-grey darkness and wind, to a snow-covered mound among the pines. But thin stripes of yellow light poked from the mound and fell across the snow, and they saw that it was a small house,

with snow piled high on its roof and plastered to its sides, until it seemed a house built of snow planks, with snow carving, snow shutters and snow sills - a house roofed with snow shingles.

Only the smoking stove-pipe poking from the roof was free of snow.

But, though the snow was so deep, the door of the house was above the frozen surface. The hunters sent frightened looks to each other. They feared that the house door was raised above the snow

because, beneath the snow, hidden, were crouched a pair of giant chicken-legs. In all the stories they had ever heard, shamans lived in houses that walked on chicken-legs. And, indeed, as they

slid nearer the house through the stinging grey mist, they heard a soft crooning, clucking noise, like that of a sleepy chicken.

The gyrfalcon wheeled around and about the little house, screaming its shrill, cold cry, and then dropped to the snow, and turned as it dropped into that pretty boy or handsome girl.

The hunters stopped, jostling into each other, those behind peering over the shoulders of those before. They had all heard, and told, stories of shamans, and to be there, in front of a shaman's

hut, was frightening, like finding the gingerbread cottage.

'Come in from the cold,' said the shaman's grandchild.

The leader slid over to the house, and took off his skis. With hissings and scrapings of wooden runners over ice, the others joined him. They stuck the skis, and their bows, upright in the snow

around the house, and they hung back, to let their leader be the first to follow the shaman's grandchild into the little house.

Once their leader had stepped through the outer door, the others crowded after, afraid to be left outside, and the small, dark space between the double doors was full of pushing and shoving until

the inner door was opened and let them into the hut's single room.

It was a wooden room, a gold and cream and white room of split wood, and its air was hung with a thin, glimmering curtain of candlelight, all dusty with wood-scented dust. In the corners, shadows

hung down from the ceiling like thick cobwebs. On the walls hung lutes, rattles, flutes and a big, oval drum, its skin painted with red signs which drew the stares of all the hunters. They knew

it for a ghost drum, the very badge of a shaman.

The light of the candles made white flares in the polish of the instruments, and deep shadows between them and the walls.

The stove had made the room so hot that the hunters sweated in their heavy clothes and tugged off their caps and mittens and opened the fronts of their coats. The shaman's grandchild knelt to

help the leader off with his boots, and the other men leaned on each other as they kicked off their own boots. The shaman's grandchild collected all their coats and hats from them, throwing them

into a heap on a chest against the wall.

In the centre of the room was a wooden table, set about with wooden benches and stools, and the table was crammed with dishes of black bread and jugs of vodka bowls of dried fish and cheese and

fruit. The hunters looked at it all, mouths watering, but too shy to ask if the food was for them. They had all been taught that a guest should be given a seat, food, drink and warmth before

being asked a single question, but they had not expected a shaman to be so welcoming.

'Sit, Uncles, eat,' said the shaman's grandchild, and the hunters clambered over benches and hooked stools to them with their feet. Before their backsides were on the wood, their hands were

reaching for the food and putting it into their mouths. They were hungry.

At the other end of the room was a small bed-closet, with wooden doors that could be closed against draughts. The doors were carved with interlacing lines, and hearts, and deer nibbling at trees whose branches were full of flowers and birds. One of the closet doors stood open, and the shaman's grandchild went over to this open door, and sat on the bed.

The hunters' leader looked up, his mouth full of bread and fish, and saw the other door of the bed-closet swing open. In the deep shadows within the bed sat someone small and hunched, peering out

at them. A little, thin hand, twisted with knots of veins, reached out into the candlelight and took the hand of the youngster who sat on the end of the bed.

The hunters' leader raised his glass of vodka to the old woman in the bed, whom he could hardly see. 'To you, Grandmother! Thank you for this welcome! Long life and good luck to you!'

From within the bed's deep shadows came an old, cracked laugh. A scraping voice, almost worn away by age and use, said, 'The long life I have had, son; the luck I have made - but I thank you for

your good wishes. Eat all you want - it's cold outside! And while you eat, tell me why you search for a shaman.'

'Here,' said the hunters' leader and, standing, he pulled free something that was tucked under his belt. He threw it to the youngster. 'Show your granny that. Can she say what kind of animal it

came from?'

The thing was a small hide, oval in shape, and covered with a long, fine hair. The youngster turned it over and over, and stroked the long hair, puzzled.

The old voice from within the bed said, 'Put it on your head, little pancake, then you will see - it's the skin and hair from a man's head.'

The leader of the hunters nodded. 'My brother's scalp.'

The youngster dropped the scalp to the floor. 'No, no,' chided the old voice. 'You don't throw your shirt from you, that's made of reindeer skin. The scalp's only skin and hair, the same.'

'Reindeer don't kill and skin each other!' said the youngster.

From inside the bed came the harsh laugh. 'Only because they can't hold a knife!'

The leader of the hunters picked up the scalp and tucked it in his belt again. 'It was done by the Czar's hunters. Have you heard of the Czar, Grandmother, who says he owns all this land and even

says he owns us?'

The old voice answered, sounding amused, 'I have heard some mention of this Czar.'

'Grandmother, the Czar has been sending his people into our Northlands - more and more of his people. They fish the rivers and lakes, they hunt our animals, they cut down the trees - '

'They're killing the land, Grandmother!' said another man.

The old woman's voice came whispering through the haze of candlelight and wood-dust. 'So my little daughter has been telling me.' Her ugly old hand pulled out a long strand of the girl's black

hair. 'Such startling news to bring an old woman - that woodcutters are felling trees, that hunters are killing animals, and fishers are killing fish! Such shocks will be the death of me!'

The youngster, the handsome girl, said, 'Grandmother, I - ' but was quiet at once when the old woman held up a skinny hand.

There was a silence in the hot, crowded little hut. They heard the fire hissing in the stove, and the house crooning to itself.

'Grandmother,' said the hunters' leader, 'it is true that we all live by killing each other. It's the way the world turns. But always before, the hunters have left alive enough animals and trees

to fill the land again; always we have sung the ghost songs, to send the ghosts safely to the Ghost World. But these hunters of the Czar, Grandmother - they don't know the ghost songs and they

mean to leave nothing alive!'

'And it's not only the beavers, the foxes, the wolves they kill, either,' said another man, and others joined in.

'No - they kill our reindeer, Grandmother! Do we go to the Czar's house and steal his gold?'

There were shouts of angry agreement, and the stamping of feet. 'Yes, killed our reindeer - and when we've tried to stop them - '

'Then they've killed us!'

Another laugh came from within the bed. 'And have you never killed men of another tribe, to take their reindeer? Men have always killed each other.'

The men's excitement died away into silence. They even stopped eating.

'That's true, Grandmother,' said the leader. 'But listen - the Czar's hunters use nets of mesh so small they empty the rivers of fish, young and old. Big catches this year, none next. They cut

down whole lands of trees. They catch birds in traps and they steal the eggs. And we, we who have always lived here, and hunted here, and kept our bargain with the animals - we must steal from

the Czar's traps if we're to eat. And then the Czar's hunters say we are stealing from him, and shoot us!'

The old shaman said, 'A sorry story, my sons. Why do you bring it to me?'

The men had nothing to say to that. They put down their glasses. They stared at each other, and looked towards the darkness of the bed-closet.

The lass said quietly, 'They want you to help them, Granny.'

'And how do they think I can help?'

'Granny, my dream - '

'Shh, shh,' said the old woman, and the lass was quiet. 'Listen to me, all of you.' The shaman leaned forward in her bed, so that the candlelight fell on her, and, for the first time, the hunters

saw her. She was more than old. She was a skeleton covered with wrinkled leather, worn thin. The flesh sagged from her brittle bones: the skin was crossed, recrossed and crumpled with many, many

lines, both deep and fine. Age had pulled down her lower lids to show the red linings, and her eyes would not properly close. Her lips sagged away from her brown teeth, and her mouth dribbled at

its ever-damp corners. A beard and moustache of fine silver hairs hung from her chin and upper lip, while her head was almost bald. Age had made her so horrible that some of the men winced at the

sight of her, but the lass sitting on the bed held the old woman's hand and watched her, as she spoke, with respect and love.

'I pitied you your wanderings in this cold,' said the shaman, 'so I sent out my little falcon to find you and bring you here. And now I tell you, eat all you can, and then go back to your homes,

to your people. There is no such help as you seek.'

The lass said, 'The Northlands are dying, Granny.'

'I have lived too long, more than three hundred years,' said the shaman, gasping, for she was running out of breath. ‘In that time I have heard many cries of, "Save us, the world is coming to an

end!" But the world never was ending. It was only changing. The world must change, always, because to be unchanging is to be nothing. Even the dead change. But living things fear change and

death.' She leaned from her bed towards the hunters. 'Listen to me! Neither I nor any shaman will halt this change for you, even if we could. Go back to your homes and people,' And the ancient

woman lay back in the shadows of her bed-closet. They could hear her breath gasping and tearing.

The men sat at the table, not eating any more, and hanging their heads. The shadows lowered from the corners of the ceiling, and the candlelight shimmered thinly over the walls and figures like

fiery water.

In the quiet came the lass's voice. 'Grandmother, I had a dream, a strong dream. I saw men coming into the Northlands, and they were all on leashes, and these leashes were all held in the hands

of a man who sat on a heap of - '

'Little daughter,' said the old woman, with hardly enough breath to speak the words, and the lass stopped speaking at once. 'You are not a shaman yet. A witch - a good witch - but no shaman. So

be quiet now.' The lass lowered her head. Her long black hair fell forward, starred with its white beads, and hid her face.

'You see how it is with me,' gasped the ancient woman after a while. 'I am the only shaman who will hear you, but even if I would help you, I could not. You see my little daughter here, my

apprentice?' She tried to heave herself up, and the lass quickly rose and went to sit at her pillow, to lift up the old woman and support her against her own shoulder. 'Three hundred years of

life my own grandmother gave me when I became a shaman - and three hundred years I waited for the birth of my apprentice. I should have gone into the Ghost World long ago, but I could not leave

my daughter alone . . . So on I have gone, and on, until I am nothing but clotted dust clinging to bones. My legs will not hold me up; my spine is both bent and unbending. This is my last act as

a shaman before going into the Ghost World - to spare you the labour of searching any further for a shaman's help. The shamans will not help you, my sons. There is no help to give. All things

must change.'

'But - ' began the leader of the men.

'But they are killing the Northlands!' rasped the old woman. 'If that is true, then you must live with the death, or you must die with it, that is all. I am going to rest now. I have a long

journey ahead of me. You may eat all you want. You may even stay to see me go to the Ghost World, if you wish. Lay me down now,' she said to the lass, and the youngster carefully laid her down in

the bed, before standing and closing the door of the bed-closet, to keep out draughts and the light.

The leader of the hunters stood and said, 'We shall go now.' The other men rose from their places, and began to pull on their boots, throwing their coats and hats to each other.

'Stay, Uncles - eat more,' said the lass, but the men would not look at her or answer. They stamped their feet into their boots, pulled on their mittens, fastened coats, and they went to the

door, opened it and crowded through.

A cold wind, thin but sharp, blew into the warmth of the little room, and crept round and round its corners, chilling it, as the door stayed open for the men to struggle out. But then the door

clapped shut, and the draught died.

The lass went over to a window and opened a shutter a little, looking out into the grey snow-mist. She saw the shapes of the men, dim in the grey, quickly growing darker, and then vanishing

altogether. She felt sadness when she could no longer see them; and she thought of them struggling home through the cold, and having nothing to tell, at the end, but how they had failed.

But they also vanish from this story (says the cat). I have no more to tell of them.

The lass returned to the bed-closet, where the hard breathing of the old shaman could be heard through the doors. She kicked a stool against the closet and sat there, dejectedly hanging her head,

so her face was hidden behind her long black hair.

The door of the bed-closet was pushed open, creaking, and the voice of the old shaman said, 'You think me cruel, little daughter, but I have learned - pull one thread, and that thread pulls

others, and those others pull still more. You cannot change one thing alone; you will always change many things, and you cannot tell what might become of that - it may be worse than what you

tried to cure.'

The lass said, 'Grandmother, I have dreamed this same dream many times. A man - the Czar - sits on a mound of cut tree-trunks and furs and carcasses of men and animals, and in his hands he holds

the leashes of many men who come here, into the Northlands. And these men, they hunt and they fish and they cut down trees. They take it all back to the Czar and make a bigger mound for him to

sit on - but he sends more hunters and more, until there is nothing left beneath the stars here but snow and tree-stumps. And then they begin making more mounds, here in the Northlands, and more

mounds, and more; and people come from the South to live on these mounds . . . But there are no northern people left and the only animals are rats and mice and fleas . . . And the new people are

lonely, lonely and sick, like animals in a cage . . .'

'A true dream,' said the shaman.

'But these hunters, Grandmother - the Czar holds them on leashes. They come at his orders. The Czar can order them to heel.'

'Do you think they would obey him?'

'Many would, Granny! And I am only a witch - I couldn't guard the whole of the Northlands - but I could spell one man. The Czar is only a man, isn't he? I could bind him with spells and make him

call his men back. And you could do it easily, Granny. I would have to go to the Czar's city, but you, you could walk into his dreams without leaving your bed. Granny - '

The old shaman sighed with a sound like sheets tearing. 'All things must change, all things must die. I will not speak one word or sing one note to stop it.'

The lass jumped to her feet angrily and said, 'Then why have I been given this dream? What use are shamans and what use is being a shaman?' She lost some of her anger when the old shaman laughed

at her.

'Shamans are no use, little pancake. Shamans are like the dreamers in the Ghost World, who dream the shamans and everything else. What use are the Northlands? What use are the reindeer people?

What use are trees and fish and falcons?' She lay back in her bed and gasped for breath, and the lass sat on her stool again. Then the old woman asked, 'Is my pyre built? Tonight I must

go.'

The lass left her stool and threw herself down on the bed by the old woman. She lowered her head to her grandmother's shoulder, as if lying against her, as she had done when younger - but the old

woman was too frail for that now: mere clotted dust and brittle bone. The lass was afraid to break her and held her weight a hair's breadth above the ancient body. The old woman put her hand on

the lass's head and stroked her fingers through strands of the long black hair, enjoying, for the last time, the way its warm smoothness snagged on her fingers, both soft and coarse, like raw

silk.

'You don't want me to go,' she said. 'But I've stayed too long already, and if I stay longer I shall break into pieces and blow away in the wind, and everything I was will be lost and gone. I

wish . . . But what use is wishing? Still, I wish that I could have taught you the ways of the Ghost World, and made you a shaman - ' Her whispering voice choked, either from weariness and lack

of breath or from grief. 'When you have seen the smoke rise for me, go to my sister in the East . . . She will teach you what I've not had time to teach, and bring you to me in the Ghost World. I

will be waiting for you. I will give you your three hundred years of life.'

The lass sat up, but her head hung and her long hair hid her face. You're going. And the land will die . . .'

The old shaman felt water fall from under the hair on to her face and arms. 'Shingebiss,' she said, using the lass's true name, 'I don't want to die, but I must. The land must die, everything

must die. It is sad - but many things are sad, and if we wept for all the sad things, we would weep the seas full and flood the Earth - and when the Earth was nothing but one great drowning sea,

then that would be so sad, we would have to weep again!' Breathlessly, painfully, she laughed.

Shingebiss's head hung lower, and she shook, but not with laughter.

The old shaman said, 'Now take me to my pyre.'

Shingebiss put on her heavy coat and hat and mittens, which she had not needed before when she had been clothed in warm feathers. She opened the doors of the bed-closet wide, and she went over to

the house doors, and opened them, and propped them open with stools. A cold, cold wind blew into the house, and the hanging shadows climbed further down the walls as candles were blown

out.

Then Shingebiss stooped over the bed and lifted the old shaman in her arms. The old woman was heavy, but Shingebiss was strong, and the weight was not too much. She carried the old woman across

the room, and out through the door.

Out from the warmth and candlelight of the house, into the darkness, the cold, of deep winter. The wind shrilled at the house corners and struck as keen across their faces as a sharp knife-blade.

The sky above was immense and black and high, freezing with stars. The white of the snow, broken by the blackness of the trees, stretched away into a grey fog of twilight, and then into deeper

and deeper darkness until it met the black of the sky. Under Shingebiss's feet the frozen crust of the snow crunched and sometimes let her sink to her ankles, but held her up. The ice glittered

against the white snow; the distant stars glittered against the black sky.

The pyre was close to the little house, among the trees. It had been built of bundles of branches, and its top was spread with a blanket, on which a thin layer of snow had fallen. With a last

heave of her back and shoulders, Shingebiss lifted the old woman on to the pyre, and carefully laid her down. Then she ran back over the snow to the little house, and brought back the shaman's

ghost drum, which she put into her hands, and a flask of drink, and a lump of smoked reindeer meat, which she laid beside the old woman.

And again Shingebiss ran back to the house, but this time she brought back, in a clay pot, fire from the stove. She climbed onto the pyre and sat, holding the pot between her mittens, and looking

at her grandmother. The freezing wind lifted her long strands of black hair and scoured her face, but still she sat there.

'Put the fire to the wood now, Shingebiss,' said the old woman.

'I'm afraid, Granny. What if I never become shaman?'

'You are sure to, my clever lass.'

'But if I don't - how will we find each other in Iron Wood?'

The old woman reached up one arm and caught one of the long, flying plaits. Gently, she pulled Shingebiss's head down towards her and said, 'Shingebiss, there is always reason to be afraid - but

whenever you poke your nose out of doors, little daughter, pack courage and leave fear at home. Do as I tell you. Go to my sister in the East, and learn from her to be a shaman. Don't love these

Northlands too much, Shingebiss. Don't go to the Czar thinking you can spell him as you would a simple, sane man of the North.'

She let go of the plait and held her apprentice's mittened hand while she panted for breath. 'He is only a man, the Czar - but he has a mind like broken glass, reflecting many things and all of

them crookedly. I have watched him in my scrying mirror. To try spelling him would be like plunging your hand into a box of sharp knives and hooks.' She tugged Shingebiss, weakly towards her. 'It

would be dangerous to try, and if you are killed before you are made a shaman, then the Ghost World Gate will open for you only once. You will lose yourself in Iron Wood, and even if I found you

there, you would not know me. Go to my sister in the East - but now get down and set the fire to the wood. I am cold up here. I want the fire!'

Shingebiss bent over and kissed her face. There were sharp spikes in the old woman's moustache and beard, which pricked, but the worn old skin was so soft that she could hardly feel it. Once the

kiss was given, there was nothing more to do or say. Shingebiss climbed down and set the fire to twigs in the bundles.

The cold was fierce, freezing, but dry. The twigs soon caught and blazed in the darkness. And they set light to the branches, and soon the fire leaped and roared through the bundles. Shingebiss

stood back from the heat and watched the glory of the flames burning on the ice against the dark.

The old, old woman lying on the pyre was silent for a while, but soon Shingebiss heard her voice lifted above the sound of the flames and wind. She was singing a song even older than she was

herself: a song which told of the journey from this world to the Ghost World, the ways which must be taken, the dangers which must be faced. As she sang, her voice weakened and faded, seeming to

come from further and further away. The last words were unheard. She was at the Gate.

The pyre burned, casting flickering flares of light over the snow and drawing back to itself long shadows. The heat drove Shingebiss further away and, though it warmed her face, made the wind at

her back yet more stiffeningly, cripplingly cold. Sparks, burning red, flew high against the black and silver of the sky, and the snow glared red as if stained with spilt blood. The good stink of

the burning wood half choked her and drove her further off.

Shingebiss stood staring at the beauty of the fire, but, in her mind, she was the gyrfalcon again, gyring, flying.

The gyrfalcon can outstare the sun. It can look down from the wing and see every pine needle, every mouse.

It can see more: it can see the harm done and the harm still to be done. It sees the trees dwindle away to cut stumps, and the city walls rear up through the snow-mist. It sees the roads dividing

up the open land, leading to more cities, and it sees the foxes, the wolves, turning into fur hats and coats. It sees the traps set and the hunts riding; it hears the screams and sees the snow

redden, and not with firelight. Foxes, mice, rats, fleas - these might live in cities. But not wolves, bear, lynx, beaver. Not trees.

And what use is it to be a shaman, if a shaman will do nothing? Crippled with cold, she limped away from the dying fire into the glowing silver mist of darkness, moon and snowlight, striped and

barred with the blackness of tree-trunks. All around her trees had been draped in strange cloaks and covers of snow; drifts had been blown into wind-smoothed curves, and over all glittered the

hard frost.

The wind tore itself on the corners of the little house as she came to the door, and in the wind the voice of old Frost whispered, 'Are you cold, child? Are you cold?' In the house

Shingebiss found her skis, and filled a pack with food. Down from the wall she took her bow and quiver of arrows. That was all she would need for her journey to the Czar's city. She was no

shaman, and never would be one. She needed no ghost drum.

Before she left she poured water on the fire in the stove and raked out the embers, so the house would die quickly. She sang it the ghost song, to tell it which way to travel, on its

chicken-legs, to find her grandmother in Iron Wood.

-*-

And so Shingebiss goes to spell the Czar (says the cat).

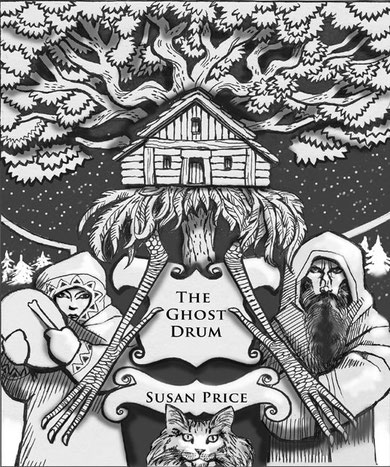

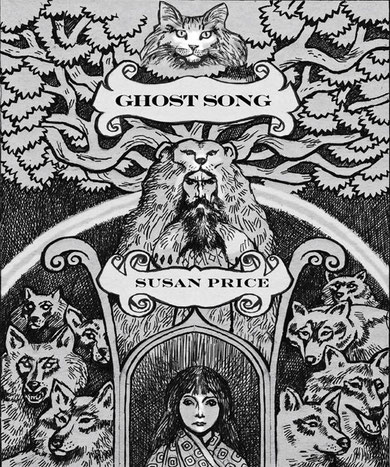

Ghost Dance is the third book in the Ghost World Sequence.

The first book is Ghost Drum, and the second Ghost Song.

Each book stands alone.

They are available on Kindle here: